This week in Napkin Math we have something special: a guest post from Marc Rubinstein of Net Interest. Net Interest is a weekly newsletter covering the financial sector and Marc is a former hedge fund manager with over 25 years of experience in and around banks and the financial sector. I think you’ll enjoy this post and highly recommend you check out his newsletter.

A few weeks ago the CEOs of the four large tech companies - Facebook, Apple, Amazon and Google - sat in front of Congress to testify. They’d been summoned to a hearing to address the issue of online platforms and market power. It was a big event. For over three hours the four men faced a grilling from legislators over their market dominance. The chair of the subcommittee overseeing the hearing set the tone:

“American democracy has always been at war against monopoly power.”

Over the course of the proceedings various analogies were thrown out there—Rockefeller’s oil empire, the railroads, Microsoft. One that didn’t receive much attention was the stock exchange. Which is ironic because while the men were speaking, billions of dollars of their stock was trading hands on a platform subject to its own monopoly scrutiny.

The stock exchange analogy is an interesting one because it highlights the fluid nature of monopoly structures. What started as a fragmented industry over two hundred years ago - first monopolised, then fragmented again - has monopolised once more. At every turn policymakers have sought to influence the outcome but consequences have not always been as anticipated.

This piece looks at how to sustain a monopoly, through the lens of the New York Stock Exchange.

From Fragmentation to Monopoly

Stock exchanges operate as simple two-sided platforms, matching buyers and sellers. Like other platforms, they benefit from network effects. The more people that transact, the greater the value of the platform to others. As traders say, “liquidity begets liquidity”.

In the days before electronic communications, it took a while to realise this benefit. In the first half of the nineteenth century, securities trading was largely local; most large cities had their own exchange. The first stock exchange in America was in Philadelphia and although New York had a slight edge as a bigger centre of trade, there wasn’t that much between them.

As technology improved in the second half of the century, that slight edge compounded. Telegraphy broadened New York’s reach and major companies in Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere increasingly wanted to list there. Trading gravitated to New York and by the end of the nineteenth century about two thirds of all domestic stock trading took place on the New York Stock Exchange. Philadelphia was left in the dust, with a 3.5% share.

For the next 100 years the New York Stock Exchange maintained its dominant position.

There are many ways to sustain a monopoly—network effects, economies of scale, proprietary technology, branding, government license. The New York Stock Exchange flaunted most of them. Network effects started things off, but economies of scale kept the wheels spinning. As it grew, the exchange was able to spread its fixed costs over more and more trading volumes. Until technology costs dropped, few others could afford the US$2 billion that NYSE spent on new technologies over the 1990s.

And as for branding—there’s nothing more iconic in finance than the sight and sound of the opening bell being rung on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

These characteristics allowed the exchange to become quite profitable. It made money by taking a small fee on every trade. In the mid 2000’s it clipped around nine cents for itself on every share traded. It was owned by its members — customers who used the exchange — and so profit maximisation wasn’t central to its existence. But those clippings were enough for it to make a generous return on capital and pay its CEO even more generous sums. (A controversy erupted in 2003 when CEO Richard Grasso was revealed to have been paid US$140 million.)

Yet the world never stands still and beneath its foundations the sands of Wall Street were shifting.

From Monopoly to Fragmentation

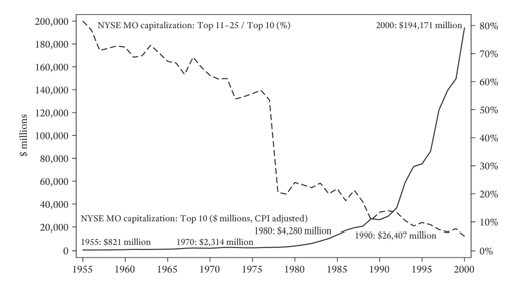

Over the 1980’s and 1990’s, the customer base of the New York Stock Exchange had begun to consolidate. Once a ragbag of small partnership firms, customers incorporated and merged into a smaller number of stronger firms. This was reflected in the membership structure of the exchange. In 1955, second-tier firms had an aggregate capitalization equal to about 80% of the capital maintained by the top 10. By 2000, this ratio had declined to less than 10%. The flipside is that power became concentrated in the hands of a few large firms—firms like Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs.

[Source]

At the same time, technology lowered the cost of establishing new, electronic venues on which to trade. Goldman Sachs for one had been spending billions on technology and by the end of the 1990’s had more than 20,000 personal computers backed by eighty trillion bytes of storage. Its size also meant that it sat on a much bigger share of trading flow than any small partnership would have had in 1955. Why pass that on to the stock exchange? Goldman could simply match buyers and sellers internally among this vast flow and avoid paying fees to the exchange.

Exploiting cheaper, faster technology, a number of alternative exchanges began to crop up. In the summer of 1999 electronic trading experts at Goldman Sachs met with the founder of one of these start-up exchanges, a company called Archipelago:

Duncan Niederauer [a fast-rising star at Goldman]… stepped to the front of the conference room and picked up a dry-erase Magic Marker. After a few introductory words, he walked to a whiteboard, wrote “NYSE,” and drew a circle around it.

“We’re going to be the electronic trading arm of the New York Stock Exchange,” Niederauer said.

The room let out a collective gasp… Goldman was going after the NYSE—using Archipelago as its Trojan horse.

[Source]

Goldman had found a way to bypass the exchange. But exchanges still enjoyed some regulatory privileges that start-ups like Archipelago couldn’t overcome. So along with other big customers of the New York Stock Exchange, they set about lobbying regulators.

It took a while, but in April 2005, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) introduced 500 pages of new regulation which finished off the New York Stock Exchange of old. Known as Regulation NMS (National Market System), it required every exchange to route order flow to all other exchanges in order to find the best price for customers. Stocks would continue to be listed on a primary exchange like NYSE (or NASDAQ in the case of the big four tech companies) but they could be traded on any exchange—including the new exchanges set up by Goldman and others.

The power shift was complete.

The erosion of NYSE’s monopoly was reflected in the declining value of membership seats. From an all-time high of US$2.65 million in the summer of 1999 (inflation adjusted the all-time high was actually back in 1929), the value of a seat fell to US$1.25 million in summer 2004.

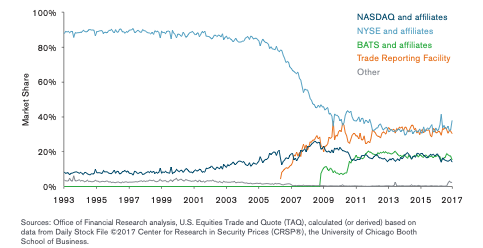

Stripped of its protections, the New York Stock Exchange demutualised and merged with Archipelago, Goldman’s Trojan horse. Meanwhile, other exchanges, non-exchange alternative trading systems and so-called dark pools managed by former NYSE members would compete for business. Today there are around 50 alternative venues open for trading US stocks outside the exchanges. In an openly competitive market, the New York Stock Exchange would go on to lose half its market share.

[Source]

But that’s not the end of the story!

From Fragmentation to Monopoly 2.0

No-one wants to lose a monopoly and the New York Stock Exchange is no different. As Peter Thiel says, “Monopoly is...not a pathology or an exception. Monopoly is the condition of every successful business.”

The first response was to consolidate. There are 13 approved stock exchanges in the US today. All but one - IEX, made famous by Michael Lewis in his book Flash Boys - are now owned by one of three publicly traded companies.

Just over a year after going public, the New York Stock Exchange merged with Euronext of Europe. Euronext itself had been formed at the beginning of the decade through the merger of the Paris, Amsterdam and Brussels bourses and LIFFE, the London International Financial Futures Exchange. The combined entity bought the American Stock Exchange and, in 2013, the whole thing was swallowed up by ICE, the Intercontinental Exchange.

This merger wave was characterised by a drive to achieve economies of scale, against the backdrop of increasing electronification of trading. In a typical merger, 25-40% of the target’s cost base can be taken out.

The second response of the exchanges is more subtle—they changed the rules of the game.

Regulation NMS, the rule that loosened the exchanges grip on their monopoly, contained a lifeline. Ever since a previous bout of deregulation, exchanges have been required to maintain a public price feed for investors. Without it, no-one would know the price of stocks from minute to minute. However, Regulation NMS allowed them to sell enhanced data – faster, richer data – at additional cost. What’s more, the same regulation made that data extremely valuable—large brokerage customers have to buy it to ensure their regulatory commitment to deliver best execution on their trading. Competitive pressure among customers and limited constraints on exchange pricing power have allowed exchanges regularly to raise prices.

In addition, stock exchanges charge fees to connect to their exchange. One of the reasons 12 exchanges are owned by three companies is that they can collect fees across 12 exchanges rather than just three. Again, there are limited constraints on pricing power as customers have no choice but to connect. Up until recently, price rises for connectivity were regularly waved through.

So while the trading part of the stock exchange business became more competitive with alternative trading venues entering the fray, the exchanges were able to clean up in the data and connectivity parts of the stack.

Regulation may have closed down one monopoly but it opened the door for another to develop.

And it’s a door the New York Stock Exchange was quick to enter. As its centre of gravity shifted away from trading towards data and connectivity, it didn’t hesitate to add to the pressure on trading margins. Lower trading fees are an inevitable consequence of a more fragmented market. Liquidity begets liquidity and so, in the effort to win it, venues compete on price. The New York Stock Exchange could afford to join in because now it had data and connectivity:

“We don't break out execution, but I don't think there's any money, I think, and we may even lose money on execution if we were to really allocate costs. And how do we make the money? Data, listings, connectivity, information… everything around the execution is where we make money.”

[Source]

There’s another way to sustain a monopoly and it’s called commoditizing the complement. Joel Spolsky identified it as a major pattern in tech companies many years ago and Gwern expanded on it. A complement is a product you usually buy together with another product, like gas and cars or babysitters and dinners out. In the exchange space, data and trading are complements. Vertical integration is the classic way to enjoy higher returns from complements, but when regulation scotches that – as it did for the exchanges – there’s an alternative.

The alternative is to give away the complement for free. Done right it can perpetuate incumbents’ long term control of markets. Competitors elsewhere in the stack are too numerous, fragmented, and low-margin to invest substantially in the infrastructure to compete. People talk about building a moat around a business, but as a correspondent of Gwern points out, the alternative is to create a desert of profitability around you.

The exchange doubled down on the strategy by buying up other data assets to shore up its position in its new core market. The New York Stock Exchange’s parent company, ICE, has made several deals in the space since its purchase of Interactive Data Corporation in 2015. Its quasi-monopolistic returns are reflected in its profit margin, which is close to 60% before tax. In spite of the money it may lose on execution, last year it earned the sixth highest profit margin among S&P 500 companies, up there with Verisign (“the toll road of the Internet”) and Visa.

The Endgame

Unsurprisingly, customers aren’t happy and they’ve recently been pushing back. A couple of these customers got their people onto the executive of the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission). At the end of 2018 the SEC refused to wave through fee increases on data feeds for the first time, opening up a struggle between the exchanges on one side and their brokerage customers on the other.

Like in other monopoly debates, the struggle descends into a definition of terms. There’s a page on the SEC’s website where all sides come together to lay down their arguments (including a schoolboy who, “having not yet finished grade 11… was surprised to discover PhDs could write something so easily renounceable.”) On the one side, exchanges argue that data and trading are inseparable ‘joint’ products, constituting a larger market. On the other side brokers look at data in a narrowly-defined way, arguing that its cost does not justify the prices charged.

The struggle is currently in deadlock with the US Court of Appeals having overturned the SEC’s intervention on legal grounds. But it highlights the ongoing dynamic that exists within a monopoly structure.

Contrary to some thinking, a monopoly doesn’t come with a lifetime guarantee. Sometimes technology can diminish the stranglehold a company has in an industry, like mobile did to fixed line telephony. Other times, regulation sets out to dismantle it. The problem with regulation is that it always involves trade-offs and the insurmountable one here is the competition that exists between traders on the one hand, looking for the best price, and exchanges on the other, as platforms to provide it. In looking to reconcile these interests, regulation created a fudge that simply shifted the monopoly up the stack.

There’s an argument that regulators should have left well alone. In his book Darkness by Design, political scientist Walter Mattli argues that in spite of their bad rep, when it comes to stock exchanges, monopolies work. He shows that mechanisms of good market governance that evolved over many decades vanished shortly after the death of the old NYSE. Now, in the era of fragmented markets, costly investments in good governance have to be balanced against the new mandate to attract liquidity to survive. He reckons that in this new fudge, everyone’s a loser.

No two monopolies are alike. And the story of the New York Stock Exchange isn’t over. But its two hundred-year history highlights the power struggle between a monopoly and its customers, and the trade-offs between a monopoly and the system. How these tensions play out determine whether the monopoly survives.

Enjoy this post? Subscribe to the Everything bundle

When you become a subscriber, you don’t just get access to my best work here at Napkin Math. You also get unlimited access to:

- Superorganizers — how the world’s smartest people organize what they know to do their best work, by Dan Shipper

- Divinations — get smarter about strategy, by Nathan Baschez

- Praxis — the modern frontier of productivity, by Tiago Forte

- Means of Creation — a live talk show about the Passion Economy, by Li Jin and Nathan Baschez

And we are constantly adding more!

If you’re not a subscriber yet, consider subscribing today:

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!