Sponsored By: Composer

Wall Street legend Jim Simons has generated 66 percent returns annually for over 30 years. His secret? Algorithmic trading.

With Composer, you can create algorithmic trading strategies that automatically trade for you (no coding required).

- Build the strategy using AI, a no-code editor, or use one of 1,000-plus community strategies

- Test the performance

- Invest in a click

The internet is like water—we take its existence for granted, but its birth was by no means pre-ordained. A constellation of inventors, organizations, and efforts all contributed to its creation. In one of her signature deep dives, Contrary writer Anna-Sofia Lesiv excavates the history of digital communication infrastructure, from the invention of the telephone to the widespread installation of fiber-optic cable and big tech’s subsidization of undersea cables. Read this chronicle to understand how the internet’s decentralized origins led to its current state as fractured spaces governed by private entities—and its implications for its future accessibility. —Kate Lee

The internet is a universe of its own. For one, it codifies and processes the record of our society’s activities in a shared language, a language that can be transmitted across electric signals and electromagnetic waves at light speeds.

The infrastructure that makes this scale possible is similarly astounding—a massive, global web of physical hardware, consisting of more than 5 billion kilometers of fiber-optic cable, more than 574 active and planned submarine cables that span a over 1 million kilometers in length, and a constellation of more than 5,400 satellites offering connectivity from low earth orbit (LEO).

According to recent estimates, 328 million terabytes of data are created each day. There are billions of smartphone devices sold every year, and although it’s difficult to accurately count the total number of individually connected devices, some estimates put this number between 20 and 50 billion.

“The Internet is no longer tracking the population of humans and the level of human use. The growth of the Internet is no longer bounded by human population growth, nor the number of hours in the day when humans are awake,” writes Geoff Huston, chief scientist at the nonprofit Asia Pacific Network Information Center.

But without a designated steward, the internet faces challenges for its continued maintenance—and for the accessibility it provides. These are incredibly important questions. But in order to grasp them, it’s important to understand the internet in its entirety, from its development to where we are today.

Unlock the power of algorithmic trading with Composer. Our platform is designed for both novices and seasoned traders, offering tools to create automatic trading strategies without any coding knowledge.

With more than $1 billion in trading volume already, Composer is the platform of choice. Create your own trading strategies using AI or choose from over 1,000 community-shared strategies. Test their performance and invest with a single click.

The theory of information

In the analog era, every type of data had a designated medium. Text was transmitted via paper. Images were transmitted via canvas or photographs. Speech was communicated via sound waves.

A major breakthrough occurred when Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876. Sound waves that were created on one end of the phone line were converted into electrical frequencies, which were then carried through a wire. At the other end, those same frequencies were reproduced as sound once again. Speech could now transcend physical proximity.

Unfortunately, while this system extended the range of conversations, it still suffered from the same drawbacks as conversations held in direct physical proximity. Just as background noise makes it harder to hear someone speak, electrical interference in the transfer line would introduce noise and scramble the message coming across the wire. Once noise was introduced, there was no real way to remove it and restore the original message. Even repeaters, which amplified signals, had the adverse effect of amplifying the noise from the interference. Over enough distance, the original message could become incomprehensible.

Still, the phone companies tried to make it work. The first transcontinental line was established in 1914, connecting customers between San Francisco and New York. It comprised 3,400 miles of wire hung from 130,000 poles.

In those days, the biggest telephone provider was the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), which had absorbed the Bell Telephone Company in 1899. As long-distance communications exploded across the United States, Bell Labs, an internal research department of electrical engineers and mathematicians, started to think about expanding the network’s capacity. One of these engineers was Claude Shannon.

In 1941, Shannon arrived at Bell Labs from MIT, where the ideas behind the computer revolution were in their infancy. He studied under Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, and worked on Vannevar Bush’s differential analyzer, a type of mechanical computer that could resolve differential equations by using arbitrarily designed circuits to produce specific calculations.

Source: Computer History Museum.It was Shannon’s experience with the differential analyzer that inspired the idea for his master’s thesis. In 1937, he submitted “A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits.” It was a breakthrough paper that pointed out that boolean algebra could be represented physically in electrical circuits. The beautiful thing about these boolean operators is that they require only two inputs—on and off.

It was an elegant way of standardizing the design of computer logic. And, if the computer’s operations could be standardized, perhaps the inputs the computer operated on could be standardized too.

When Shannon began working at Bell Labs during the Second World War, in part to study cryptographic communications as part of the American war effort, there was no clear definition of information. “Information” was a synonym for meaning or significance, its essence was largely ephemeral. As Shannon studied the structures of messages and language systems, he realized that there was a mathematical structure that underlied information. This meant that information could, in fact, be quantified. But to do so, information would need a unit of measurement.

Shannon coined the term “bit” to represent the smallest singular unit of information. This framework of quantification translated easily to the electronic signals in a digital computer, which could only be in one of two states—on or off. Shannon published these insights in his 1948 paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” just one year after the invention of the transistor by his colleagues at Bell Labs.

The paper didn’t simply discuss information encoding. It also created a mathematical framework to categorize the entire communication process in this way. For instance, Shannon noted that all information traveling from a sender to a recipient must pass through a channel, whether that channel be a wire or the atmosphere.

Shannon’s transformative insight was that every channel has a threshold—a maximum amount of information that can be delivered reliably to a sender. As long as the quantity of information carried through the channel fell below the threshold, it could be delivered to the sender intact, even if noise had scrambled some of the message during transmission. He used mathematics to prove that any message could be error-corrected into its original state if it traveled through a large-enough channel.

The enormity of this revolution is difficult to communicate today, mainly because we’re swimming in its consequences. Shannon’s theory implied that text, images, films, and even genetic material could be translated into his informational language of bits. It laid out the rules by which machines could talk to one another—about anything.

At the time that Shannon developed his theory, computers could not yet communicate with one another. If you wanted to transfer information from one computer to the other, you would have to physically walk over to the other computer and manually input the data yourself. However, talking machines were now an emerging possibility. And Shannon had just written the handbook for how to start building it.

Switching to packets

The telephone system was the only interconnected network by the mid-20th century. AT&T was the largest telephone network at the time. It had a monstrous continental web with hanging copper wires criss-crossing across the continent.

The telephone network worked primarily through circuit switching. Every pair of callers would get a dedicated “line” for the duration of their conversation. When it ended, an operator would reassign that line to connect other pairs of callers, and so on.

At the time, it was possible to get computers “on the network” by converting their digital signals into analog signals, and sending the analog signals through the telephone lines. But reserving an entire line for a single computer-to-computer interaction was seen as hugely wasteful.

Leonard Kleinrock, a student of Shannon’s at MIT, began to explore the design for a digital communications network—one that could transmit digital bits instead of analog sound waves.

His solution, which he wrote up as his graduate dissertation, was a packet-switching system that involved breaking up digital messages into a series of smaller pieces known as packets. Packet switching shared resources among connected computers. Rather than having a single computer’s long communiqué take up an entire line, that line could instead be shared among several users’ packets. This design allowed more messages to get to their destinations more efficiently.

For this scheme to work, there would need to be a network mechanism responsible for granting access to different packets very quickly. To prevent bottlenecks, this mechanism would need to know how to calculate the most efficient, opportunistic path to take a packet to its destination. And this mechanism couldn’t be a central point in the system that could get stuck with traffic—it would need to be a distributed mechanism that worked at each node in the network.

Kleinrock approached AT&T and asked if the company would be interested in implementing such a system. AT&T rejected his proposal—most demand was still in analog communications. Instead, they told him to use the regular phone lines to send his digital communications—but that made no economic sense.

“It takes you 35 seconds to dial up a call. You charge me for a minimum of three minutes, and I want to send a hundredth-of-a-second of data,” Kleinrock said.

It would take the U.S. government to resolve this impasse and command such a network into existence. In the late 1960s, shaken by the Soviet Union’s success in launching Sputnik into orbit, the U.S. Department of Defense began investing heavily in new research and development. It created ARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency, which funded various research labs across the country.

Robert Taylor, who was tasked with monitoring the programs’ progress from the Pentagon, had set up three separate Teletype terminals for each of the ARPA-funded programs. At a time when computers cost anywhere from $500,000 to several million dollars, three computers sitting side-by-side seemed like a tremendous waste of money.

“Once you saw that there were these three different terminals to these three distinct places the obvious question that would come to anyone's mind [was]: why don't we just have a network such that we have one terminal and we can go anywhere we want?” Taylor asked.

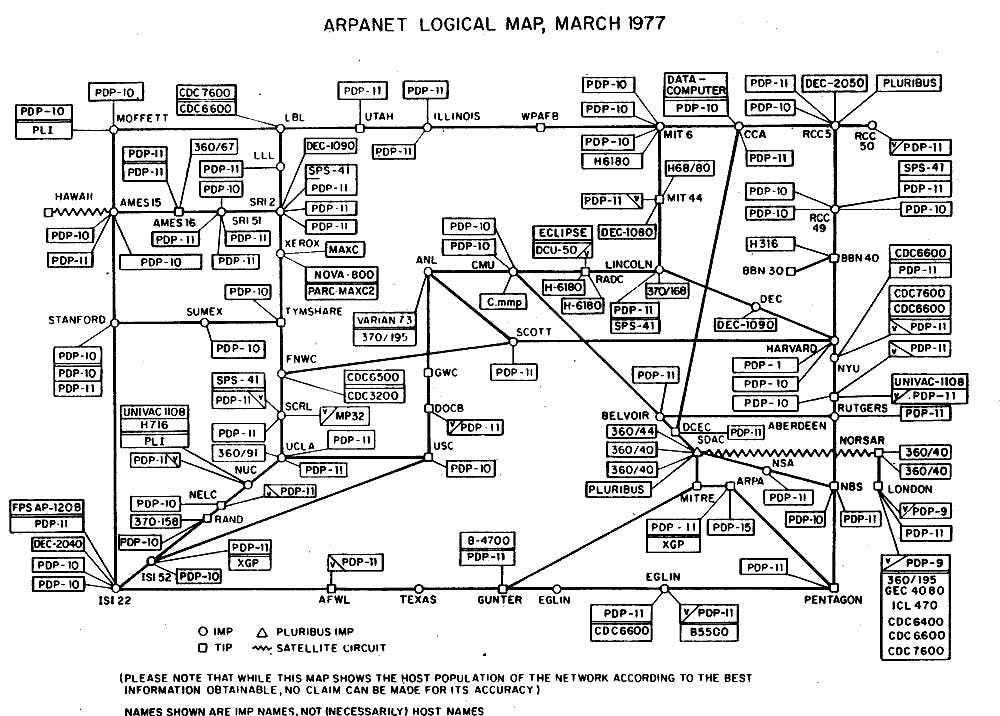

This was the perfect application for packet switching. Taylor, familiar with Kleinrock’s work, commissioned an electronics company to build the types of packet switchers Kleinrock had envisioned. These packet switchers were known as interface message processors (IMPs). The first two IMPs were connected to mainframes at UCLA and Stanford Research Institute (SRI), using the telephone service between them as the communications backbone. On October 29, 1969, the first message between UCLA and SRI was sent. ARPANET was born.

ARPANET grew rapidly. By 1973, there were 40 computers connected to IMPs across the country. As the network grew faster, it became clear that a more robust packet-switching protocol would need to be developed. ARPANET’s protocol had a few properties that prevented it from scaling easily. It struggled to deal with packets arriving out of order, didn’t have a great way to prioritize them, and lacked an optimized system to deal with computer addresses.

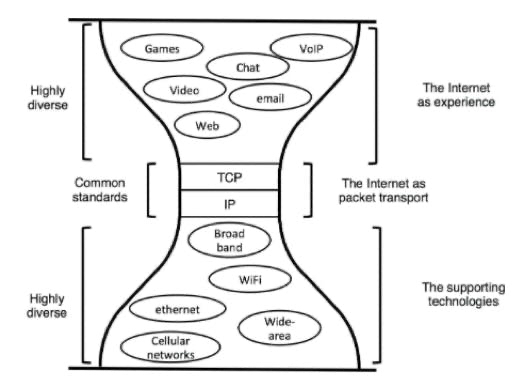

Source: Computer History Museum.By 1974, researchers Vinton Cerf and Robert Khan came out with “A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication.” They outlined the ideas that would eventually become Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP)—the two fundamental standards of the internet today. The core idea that enabled both was a “datagram,” which wrapped the packets in a little envelope. That envelope would act as a little header at the front of each packet that would include the address it was going to, along with other helpful bits of info.

In Cerf and Khan’s conception, the TCP would run on the end-nodes of the network—meaning that it wouldn’t run on the routers and obstruct traffic, but instead on users’ computers. The TCP would do everything from breaking messages into packets, placing the packets into datagrams, ordering the packets correctly at the receiver’s end, and performing error correction.

Packets would then be routed via IP through the network, which ran on all the packet-directing routers. IP only looked at the destination of the packet, while remaining entirely blind to the contents it was transmitting, enabling both speed and privacy.

These protocols were trialed on a number of nodes within the ARPANET, and the standards for TCP and IP were officially published in 1981. What was exceedingly clever about this suite of protocols was its generality. TCP and IP did not care which carrier technology transmitted its packets, whether it be copper wire, fiber-optic cable, or radio. And they imposed no constraints on what the bits could be formatted into—video text, simple messages, or even web pages formatted in a browser.

Source: David D. Clark, Designing an Internet.

This gave the system a lot of freedom and potential. Every use case could be built and distributed to any machine with an IP address in the network. Even then, it was difficult to foresee just how massive the internet would one day become.

David Clark, one of the architects of the original internet, wrote in 1978 that “we should … prepare for the day when there are more than 256 networks in the Internet.” He now looks upon that comment with some humor. Many assumptions about the nature of computer networking have changed since then, primarily the explosion in the number of personal computers. Today, billions of individual devices are connected across hundreds of thousands of smaller networks. Remarkably, they all still do so using IP.

Although ARPANET was decommissioned in 1986, the rest of the connected computers kept going. Residences with personal computers used dial-up to get email access. After 1989, a new virtual knowledge base was invented with the World Wide Web.

With the advent of the web, new infrastructure, consisting of web servers, emerged to ensure the web was always available to users, and programs like web browsers allowed end nodes to view the information and web pages stored in the servers.

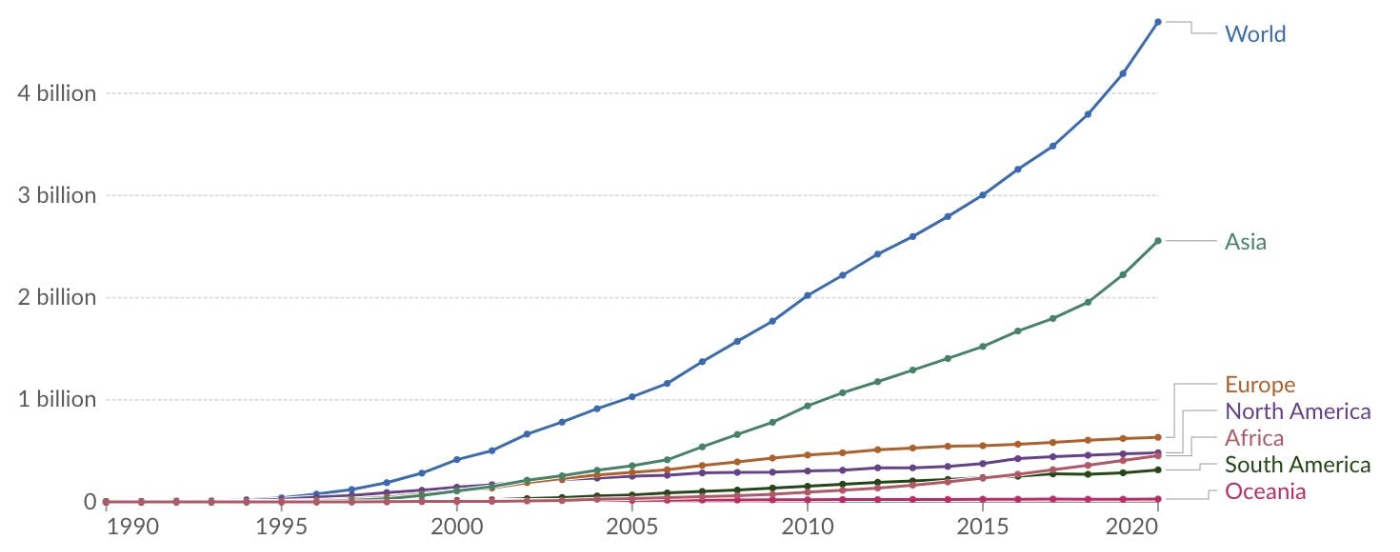

Source: Our World in Data.As the number of connected people increased in hockey-stick fashion, carriers finally began realizing that dial-up—converting digital to analog signals—was not going to cut it anymore. They would need to rebuild the physical connectivity layer by making it digital-first.

The single biggest development that would enable this and alter the internet forever was the mass installment of fiber-optic cable throughout the 1990s. Fiber optics use photons traveling through thin glass to increase the speed of information flow. The fastest connection possible with copper wire was about 45 million bits per second (mbps). Fiber optics made that connection more than 2,000 times faster. Today, residences can hook into a fiber-optic connection that can deliver them 100 billion bits per second (gbps).

Fiber was initially laid down by telecom companies offering high-quality cable television service to homes. The same lines would be used to provide internet access to these households. However, these service speeds were so fast that a whole new category of behavior became possible online. Information moved fast enough to make applications like video calling or video streaming a reality.

The connection was so good that video would no longer have to go through the cable company’s digital link to your television. It could be transmitted through those same IP packets and viewed with the same experience on your computer.

YouTube debuted in 2004 and Netflix began streaming in 2007. The data consumption of American households skyrocketed. Streaming a film or a movie requires about 1 to 3 gigabytes of data per hour. In 2013, the median household consumed 20-60 gigabytes of data per month. Today, that number falls somewhere about 587 gigabytes.

And while it may have been the government and small research groups that kickstarted the birth of the internet, its evolution henceforth was dictated by market forces, including service providers that offered cheaper-than-ever communication channels and users that primarily wanted to use those channels for entertainment.

A new kind of internet emerges

If the internet imagined by Cerf and Kahn was a distributed network of routers and endpoints that shared data in a peer-to-peer fashion, the internet of our day is a wildly different beast.

The biggest reason for this is that the internet today is not primarily used for back-and-forth networking and communications—the vast majority of users treat it as a high-speed channel for content delivery.

In 2022, video streaming comprised nearly 58 percent of all Internet traffic. Netflix and YouTube alone accounted for 15 and 11 percent, respectively.

This even shows up in internet service provision statistics. Far more capacity is granted for downlink to end nodes than for uplink—meaning there is more capacity to provide information to end-user nodes than to send data through networks. Typical cable speeds for downlink might reach over 1,000 mbps, but only about 35 mbps are granted for uplink. It’s not really a two-way street anymore.

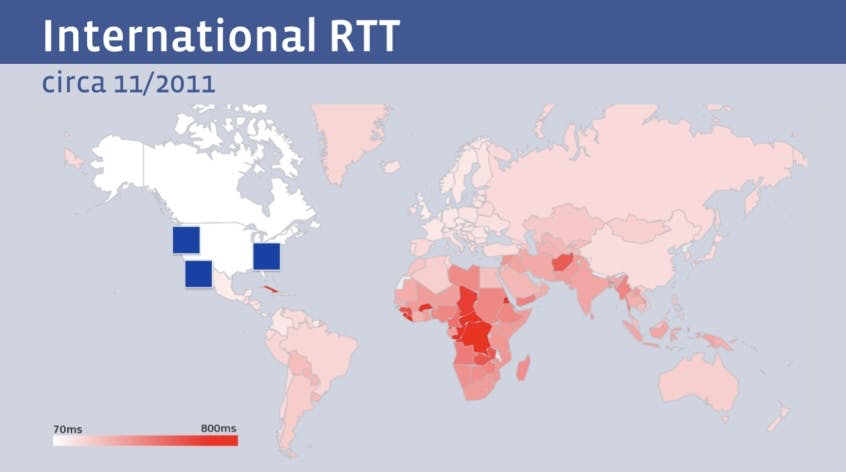

Even though the downlink speeds enabled by fiber were blazingly fast, the laws of physics still imposed some harsh realities for global internet companies with servers headquartered in the United States. The image below shows the “round-trip time” for various global users to connect to Facebook in 2011.

Source: Geoff Huston.At the time, Facebook users in Asia or Africa had a completely different experience to their counterparts in the U.S. Their connection to a Facebook server had to travel halfway around the world, while users in the U.S. or Canada could enjoy nearly instantaneous service. To combat this, larger companies like Google, Facebook, Netflix, and others began storing their content physically closer to users through CDNs, or “content delivery networks.”

These hubs would store caches of the websites’ data so that global users wouldn’t need to ping Facebook’s main servers—they could merely interact with the CDNs. The largest companies realized that they could go even further. If their client base was global, they had an economic incentive to build a global service infrastructure. Instead of simply owning the CDNs that host your data, why not own the literal fiber cable that connects servers from the United States to the rest of the world?

In the 2020s, the largest internet companies have done just that. Most of the world’s submarine cable capacity is now either partially or entirely owned by a FAANG company—meaning Facebook (Meta), Amazon, Apple, Netflix, or Google (Alphabet). Below is a map of some of the sub-sea cables that Facebook has played a part in financing.

Source: Telegeography.These cable systems are increasingly impressive. Google, which owns a number of sub-sea cables across the Atlantic and Pacific, can deliver hundreds of terabits per second through its infrastructure.

In other words, these applications have become so popular that they have had to leave traditional internet infrastructure and operate their services within their own private networks. These networks not only handle the physical layer, but also create new transfer protocols —totally disconnected from IP or TCP. Data is transferred on their own private protocols, essentially creating digital fiefdoms.

This verticalization around an enclosed network has offered a number of benefits for such companies. If IP poses security risks that are inconvenient for these companies to deal with, they can just stop using IP. If the nature by which TCP delivers data to the end-nodes is not efficient enough for the company’s purposes, they can create their own protocols to do it better.

On the other hand, the fracturing of the internet from a common digital space to a tapestry of private networks raises important questions about its future as a public good.

For instance, as provision becomes more privatized, it is difficult to answer whose shoulders the responsibility of providing access to the internet as a “human right,” as the U.N. describes, will fall on.

And even though the internet has become the de facto record of recent society’s activities, there is no one with the dedicated role of helping maintain and preserve these records. Already, the problem known as link rot is beginning to affect everyone from the Harvard Law Review, where, according to Jonathan Zittrain, three quarters of all links cited no longer function. This occurs even at The New York Times, where roughly half of all articles contain at least one rotted link.

The consolation is that the story of the internet is nowhere near over. It is a dynamic and constantly evolving structure. Just as high-speed fiber optics reshaped how we use the internet, forthcoming technologies may have a similarly transformative effect on the structure of our networks.

SpaceX’s Starlink is already unlocking a completely new way of providing service to millions. Its data packets, which travel to users via radio waves from low earth orbit, may soon be one of the fastest and most economical ways of delivering internet access to a majority of users on Earth. After all, the distance from LEO to the surface of the Earth is just a fraction of the length of subsea cables across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Astranis, another satellite internet service provider that parks its small sats in geostationary orbit, may deliver a similarly game-changing service for many. Internet from space may one day become a kind of common global provider. We will need to wait and see what kind of opportunities a sea change like this may unlock.

Still, it is undeniable that what was once a unified network has, over time, fractured into smaller spaces, governed independently of the whole. If the initial problems of networking involved the feasibility of digital communications, present and future considerations will center on the social aspects of a network that is provided by private entities, used by private entities, but relied on by the public.

Anna-Sofia Lesiv is a writer at venture capital firm Contrary, where she originally published this piece. She graduated from Stanford with a degree in economics and has worked at Bridgewater, Founders Fund, and 8VC.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!