Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

The average business book is a blog post stretched to 250 pages by an underpaid ghost writer who hates what their life has become.

That said, there are some that really do matter. A select few books pass the sniff test either by a.) offering robust data analysis that can be analyzed by outside experts, such as The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen, or b.) relying on case studies from the author’s unique experiences and putting forward a genuinely novel business idea, such as High Output Management by Andy Grove. By my count, the number of books that satisfies either of these conditions is fewer than 30.

Today, I’m excited to announce that there is a new book that deserves to be added to that painfully short list of required reading: Pattern Breakers: Why Some Startups Change the Future by Mike Maples, Jr. and Peter Ziebelman.

In Pattern Breakers, the venture-capitalist authors tackle a core conundrum of startups: Many of the most successful startups pivoted from their original business idea. Slack started as a video game company before conquering at-work communication, Pinterest began as a mobile shopping app called Tote before turning to image-sharing and social media, and YouTube was initially a video dating site with the slogan “Tune In, Hook Up.”

The book is almost entirely written in Maples's voice and from his perspective as a successful seed investor at the venture capital firm Floodgate, whose winners include Lyft, Twitch, Okta, and Chegg. A few years ago, Maples noticed that “something like 80 percent of [his] investment profits had come from pivots”—those companies that started by doing one thing and then found success doing something tangentially related or altogether different.

This was an uncomfortable realization for Maples. If his biggest winners were pivots, does that mean he just got lucky? Or did he invest in the wrong companies but the right people—those self-aware enough to pivot? As for the rest of us: If this is what a successful investor looks like, what does that mean for everyone else looking to start or pick the next great startup? It could be that we are doing the whole startup thing wrong.

Maples and Ziebelman (who works a different fund from Maples and lectures at Stanford Business School) teamed up to figure this conundrum out. Their answer is to propose a new theory of startup formation they call inflection theory, which has wholly shifted my perspective on company building—and I think it can do the same for you.

Startup success starts earlier than you think

Making a better product is a good way for a startup to die. Incumbents are so powerful that in order to challenge them, startups usually need to offer something radically different rather than simply something superior to what already exists. The only way to win is to completely alter the paradigm in such a way that incumbents can’t reconcile it with their current mode of operating. Airbnb beat Marriott not by offering a better hotel, but by offering a stay at a local’s home—a product Marriott was wholly unequipped to match.

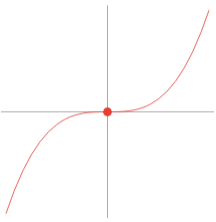

What startups are looking for is called an inflection point. In mathematics, an inflection is a change in a curve, the point where things start changing.

Source: Wolfram Alpha.

Inflection theory takes this same bend-in-the-curve idea and applies it to the world beyond math. An inflection can be a large change in technology (such as LLMs), in regulation (the allowance of cross-state telehealth services), in consumer culture (such as the dawning age of digital minimalism), or in any other significant arena.

Successful founders are able to time these inflection points so that when the world starts to change, they are ready, such as creating software products that benefit from LLMs in 2021 or from smartphones in 2008. Crucially, these founders are also, through fortuitous coincidences of history and skill sets, uniquely suited to these markets. For example, now is an excellent time to be working in biotech. We’ve hit an inflection point on what you can do with deep learning and biology. There are billions of dollars to be made—if a founder can understand the science.

Inflection points also explain the pivot conundrum of startups. A founder’s initial job is not to even have an idea. It is to discover inflection points. Once they have discovered an inflection point, they must derive an insight from them. What’s an insight? The authors say it’s a “non-obvious truth about how one or more inflections can be harnessed to change human capacities and behaviors.” A properly applied insight will harness “one or more inflections to radically change human capacities and behavior.”

Only then do the founders start worrying about the question of what their company will sell. Pointing out how the world is changing is easy: It is simple to state a truth like, “Large language models will change the world.” It is enormously challenging to specify how the change will occur and what new behaviors it will enable. It is only when they’ve nailed the latter that great founders start to think up an idea for their startup.

So many of our greatest companies undergo pivots because the inflection point and subsequent insight can be applied to multiple ideas. Take this very publication: We originally thought we could build a bundle of every type of business writer. Our insight was that the creator economy could enable a new type of expert-led publication to be built. For various reasons, we were wrong. However, that insight around the creator economy and empowering experts also neatly translated into our current version of the company, where we still empower expert writers but also make software around the ideas they have. Our insight—that creators would be amazing distribution engines—stayed the same, but we pivoted our idea from a bundle of many writers to a publication with fewer writers more focused on creating niche products.

Finally, even if you have identified an inflection point, insight, and idea that makes sense, it still is not enough. Venture-backed startups are fighting to change the world, so if you have any smaller amount of ambition, the risk-to-reward ratio doesn’t make sense. To do so requires a movement that believes in the idea. And as any adherent of PETA, Mormonism, or Crossfit will tell you, you need to have true believers to do so. One reason for which ChatGPT and its ilk have become so popular is because publications like this one have become missionaries for the technology.

Knowing that you have to have all four in conjunction—an inflection, insight, idea, and movement—it’s clear why the failure rate of startups is so high. This stuff is challenging! And then, to make the challenge harder, you have to scale the damn thing to make hundreds of millions in revenue.

All of this information is contained in the first 100 pages or so of Pattern Breakers. The authors introduce the idea in the first part of the book and devote about 130 pages to telling founders how to pressure-test their assumptions at each stage of the process. To prove their points, they rely on Maples’s investing career, drawing out fun, succinct narratives about the founding of companies like Twitch—which was originally streaming cofounder Justin Kan’s life online before pivoting to video games—that prove his point.

Even though the argument is convincing, I do not find this analysis, as described, very rigorous. In a podcast appearance, Maples said that he had “a database of any startup where you would have made more than 100x on your first check.” He used this database to interview founders, review their early pitch decks, and try to understand how they had such a great return.

To improve their process, they could have published the database and done the napkin math. What sectors were these companies in? How many pivots did they have? Was there a relationship between time to pivot and exit size? Without the sample size, we are left to rely on the author’s demonstrably great expertise. Floodgate is a great fund! These guys have great résumés! It is possible they did that work and I’m being overly cautious, but the amount of research they conducted is unclear. If they had published seriously rigorous analysis, this could have been a nuclear-level business bestseller. The best writers show their work.

Why inflection theory matters

For most of my career in startups, the right way to build was some variation on The Lean Startup by Eric Ries. While the verbage differed based on who was espousing the gospel of lean, it was essentially about deeply understanding a customer’s problem and solving it for them as cheaply as possible. Ries was so confident in his method that he wrote, “Startup success can be engineered by following the process, which means it can be learned, which means it can be taught.”

Since the failure rates for startups haven't budged since the book was published in 2011 (99 percent failed both then and now), it’s clear that the formation of world-changing companies cannot simply be engineered.

Inflection theory explains why the lean startup methodology in isolation fails. It shows that a startup is movement-dependent. It does not matter how well you follow some process. If there isn’t a shift in the way the world functions, there is nothing meaningful enough for a founder to take advantage of. Uber needed our phones to have GPS, while Snapchat needed front-facing cameras and evolving relationships with social media.

I’ve asked the same question as the authors for several years now. Why can’t we figure out how to make business strategy a science? What are the ingredients for a successful company? All of my arguments have centered on the idea that the craft of company building is a deeply fuzzy art. I’ve done most of my research on the internal variables of company success, pointing out that it is hard to quantify things around culture and taste that drive excellence.

Inflection theory matters because it is the first framework, I feel, that correctly posits the relationship between market changes and company excellence. It is now the single best way to answer the “Why now?” question every startup faces.

You can build an incredibly design-driven culture (Airbnb) or radically open data-driven culture (Meta) and have both grow incredibly quickly because the important variable wasn’t the culture, it was the insights the founder was generating. Of course those characteristics contributed to the companies’ success. But they were downstream of that initial insight from the founders.

Perhaps the strongest case for inflection theory is that it had me furiously scribbling down startup ideas. It took vague inflections I had noticed in the world—changes in media, LLMs, enterprise software—into insights and ideas. I can’t remember the last time a business book made me feel empowered as a founder. I’m now looking for inflection points everywhere.

Weaknesses and questions

The second half of the book is devoted to the implications of applying inflection theory to company management. Chapters are devoted to building a movement with employees, the importance of storytelling, and how to be disagreeable but not a jerk. These sections were weaker. They read as Maples’s (highly qualified) advice based on what he had seen work rather than anything based on rigorous study. I could think of counter-examples where founders had acted in the manner opposite of what they suggested and still been successful.

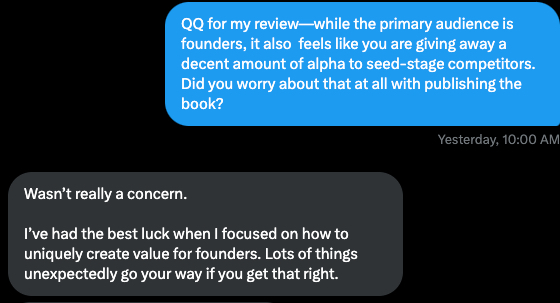

Still, inflection theory is such a valuable lens through which to examine startup ideas that I was surprised the authors gave the insight away. I asked Maples about it over direct messages on X.

Source: Screenshot by the author.

Silicon Valley has a funny, dual-deity religion. Adherents such as myself and the authors of Pattern Breakers worship both the capitalist nature of startups and the technological progress that they create. The last 40 years have proven Maples’s intuition correct—if we just do our best to help each other and rapidly improve the human condition through technology, the alpha will take care of itself.

In that spirit, I hope that this book receives a sequel. Inflection theory is novel and potentially meaningful enough that it deserves to progress from theory to provable hypothesis. Spin up a lab with a few business strategy Ph.D.s and set them to work building the data set around how often inflection theory is predictive. Then, once the research is done, create an actionable framework—either a course or lecture series where founders are trained in the gospel of Inflection.

Armed with that kind of business advice book—the super-rare kind that’s worth reading and re-reading—maybe we can all be better at spotting those inflections in the world as they’re happening, and not just once they’ve occurred.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Excellent & thanks.

Exactly, Evan--"If they had published seriously rigorous analysis, this could have been a nuclear-level business bestseller. The best writers show their work." Thank you for the context. Thank you for clarifying why Every is no longer the company I fell in love with. I respect your decision to become a software business. It is your pivot. It is your life.

like this one a lot....sent note to my son who lives in Salt Lake City and media entrepreneur he should reach out and meet you ! thanks for all the great writing. best Craig

This is great, really enjoyed this. Love the density of the summary / review. Would be interested to see this concept applied in future essays!

This is great Evan, I was missing out on Every episodes but this one really put me back in touch with the writing.

What are the other 30 odd.books which passed your sniff test?!

Thanks, I bought the book. But if the inflection theory has merits, then how Maples managed to overlook AirBnB?