Sponsored By: Sunsama

This essay is brought to you by Sunsama, your planning assistant designed for deep, focused work.

Last week, I kicked off a three-part series about the way I approach building software products. This is part II, so if you’re curious about how to build new software products that users love, start by reading the first part.

You’ve decided that you want to build something. You came up with a bunch of ideas, honed in on one, and created dedicated time to focus on building. Now what?

This week I’ll cover steps 4-6 of my approach to building products:

- Coming up with ideas

- Deciding to pounce

- Creating the time and space to build

- Shaping the idea into a simple v1

- Programming

- Design

- Getting and interpreting feedback

- Positioning

- Launching

The first one—step number 4—is the most important of all.

4. Shaping the idea into a simple v1

It’s relatively easy to generate good high-level ideas, but shaping those ideas into a good first version—deciding exactly what to build and how, and what not to build—is much more difficult. It’s where things go wrong most often.

The most common mistake is succumbing to the temptation to add too much complexity. People want their ideas to seem important and valuable, so they think it’s better to add a lot of features. I am here to tell you that this is a destructive impulse. Unlike school assignments or intern projects, you get no points for seeming like you worked hard. Nobody cares. The only thing that matters is whether a user A) finds out about it, B) immediately understands why it’s useful, and C) intuitively understands how to use it. Complexity is a drag on each of these. People don’t tell friends or coworkers about complex products that are hard to understand. They certainly don’t sign up for them. And if a lengthy explanation is required to learn to use the product, hardly anyone will bother.

So how can we achieve simplicity? You may hear that simplicity takes a lot of complex effort, but that’s not necessarily true. You don’t have to design 100 variations to arrive at the perfectly simple thing. Often, I scope a v1 in a way that feels obvious to me, and it works.

I iterate along the way, but only in response to real problems, rather than imagined ones. My process goes something like this: make a simple v1 without overthinking it, use it and show it to some test users, see what problems arise, then fix them. It’s so much faster and more effective than filling a notebook with 100 variations. The exception to this rule is at big companies, where it can make sense to do this if you need to convince skeptical execs and managers of the thoroughness of your thought process. But when it’s just you and your users, there’s no need to create a Potemkin village of middling ideas.

With Lex I knew there would be two main screens to start: the list of documents and the document editor. I knew I wanted to have one or two AI features that would be useful and make for a cool demo. I knew I wanted it to work on mobile as well as desktop. And I knew I wanted it to feel like a Google Doc, but simpler and faster.

I can’t tell you exactly why I thought those features were most important while others (like templates or custom fonts) weren’t. It comes down to intuition, which is usually sufficient when you’re building a product for yourself. If you’re building for others, you’ll need to spend more time and energy doing user research, and you shouldn’t expect to be able to achieve the same depth of fit.

Products are like works of art, in that every single detail matters and either support or detracts from the overall gestalt. If you’re not designing for yourself, it’s going to be hard to compete on equal terms with someone who is—especially if you’re operating in a market where decisions are more likely to be made based on feelings than lists of features. It’s one reason why I almost exclusively work on things that I want to use myself. (The other reason is that I find it more fun and motivating to build things I think are cool than to solve someone else’s problems.)

I don’t spend a lot of time documenting what the v1 should be. I write notes explaining the motivation and philosophy behind the product, and to brainstorm ideas and save them for later, but I don’t create a final “spec” or exhaustive plan of what the v1 should do.

Software is a living system that should continuously evolve. Sure, we can stick a flag at a moment in the timeline and call it a “ready-to-launch” v1, but that’s a somewhat arbitrary point in time. The product should be usable before that point, and it should keep evolving long after. What’s more important is to cultivate an organic vision that lives inside your head. Writing documents is a means to this end, and it’s much more effective when you see it as such. The tao that can be named is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be spoken is not the eternal Name. And the product vision that can be written down is not the true product vision.

One corollary is that you should get started coding as soon as you can. Don’t wait until you have it all figured out.

Mondays can be rough, especially when you're logging into work and you are suddenly overwhelmed with Slack messages, e-mails, calendar invites, and other work-related notifications. Sunsama is here to carry the load and help you focus on what matters. It's a planning assistant designed for deep work. It integrates with the tools you already use like Notion, Slack, and Gmail so you can just drag and drop any task to plan your focused work sessions.

Thousands of high achievers at Uber, Spotify, and other get-stuff-done companies use Sunsama every day to get a focused view of everything they need to accomplish across every tool they use and create a better work-life balance.

5. Programming

Your most important decision in this step is whether your priority is building cool products or learning cool engineering techniques. It’s alright to be interested in both, but it helps if you have a gut feeling about which is more important to you. I love writing code, but I will always care about product more. Code is a means to an end.

If the same is true for you, it’s important to filter any engineering advice you receive with one question: does the person giving it to me understand what my goals are? Most engineering advice is still going to generally be good, but you should take it with a grain of salt, because most of the time it’s targeted at people who write code professionally inside large organizations. Most of the principles they live by will also be useful to you, but not all of them.

For example, if your goal is to have an engineering career working at tech companies, it helps to stay on top of new languages and frameworks. But if you just want to build a cool product, stick with what you know.

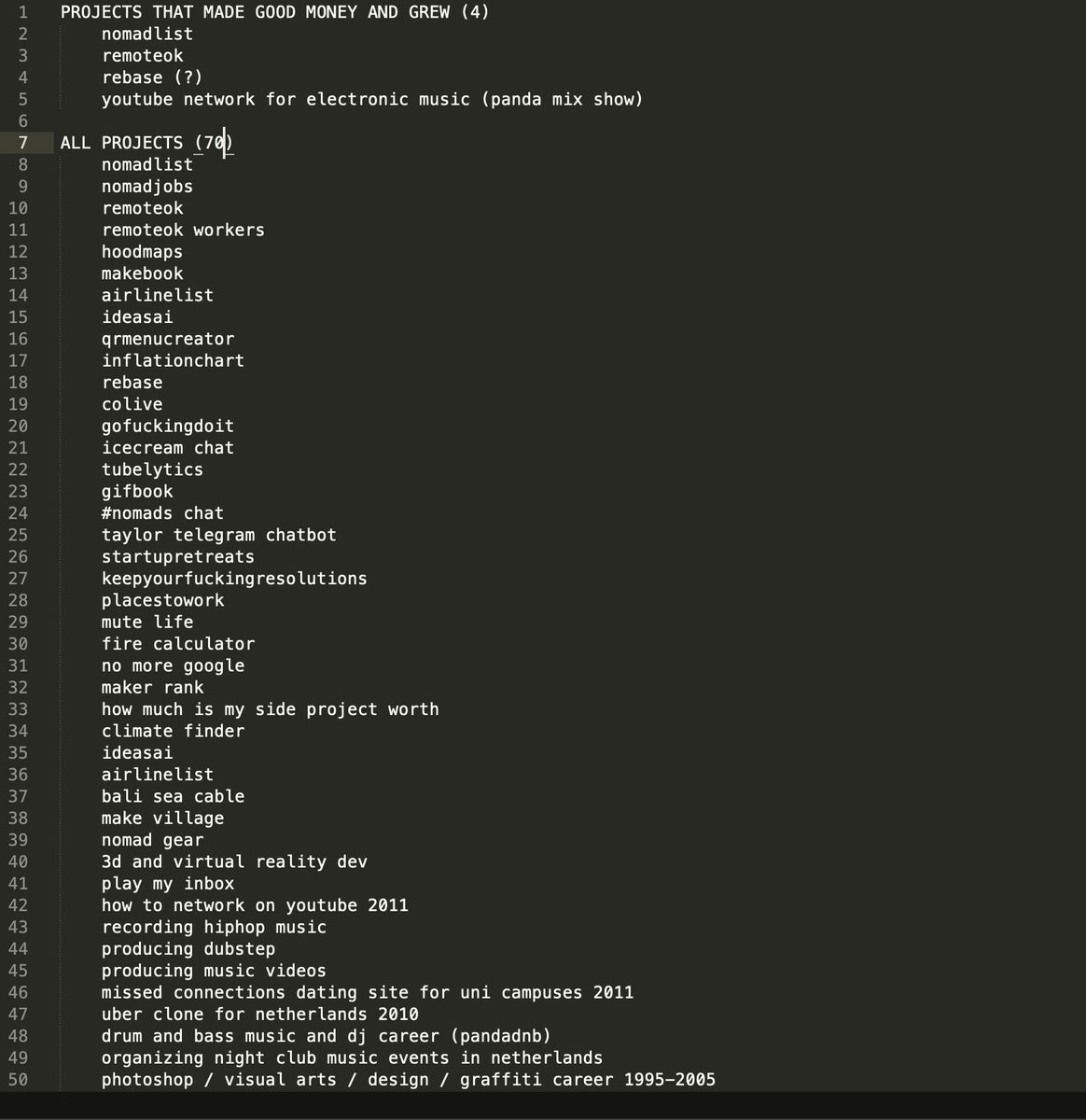

Someone who does this really well—perhaps to a fault—is Pieter Levels, who’s built a collection of valuable businesses (Nomad List, Remote OK, and now Avatar AI and Interior AI) by using the most basic technology possible and focusing purely on shipping.

He’s also prolific. Most of his ideas didn’t become mainstream products or make money, but that’s OK, because he has built a lot of ideas, and the few hits are all that matters:

Pieter has a distinct approach: he does everything himself and doesn’t build VC-style businesses that are going to IPO. But even for founders wanting to go the VC route, his approach is underrated.

The biggest mistake a startup can make is having a technical co-founder who is more interested in engineering than product-market fit. While these types of people will never come out and say that explicitly, you can infer it through their actions. If they spend a lot of energy building systems and processes and setting up cutting-edge frameworks that don’t have an obvious necessary purpose instead of simpler alternatives, it’s a sign they care more about engineering than product-market fit.

But it is possible to go too far to the other extreme. For instance, you can limit yourself by using the wrong tools: it would be an obviously wrong choice to build a modern web application in Fortran. It’s also probably suboptimal to build in PHP these days. For me, the sweet spot is Rails and React. Both technologies have been around for a long time and have big ecosystems of tools to help me move faster. They are neither archaic nor cutting-edge.

The other big mistake people make when going “too scrappy” is using it as an excuse to be sloppy. Programming is like writing: the more you do it, the easier it is to generate clean, clear output quickly—but only if at every step of the way you care about cleanliness and clarity. If your only goal is to go fast, and you never stop to think (or learn) about how to do it well, you won’t improve much. Practice makes permanent—not perfect.

To this end, you should practice good code organization, write tests, refactor after you get a feature initially working, etc. It will slow you down a little bit today, but it compounds over time and pays huge dividends later.

The fastest way to learn how is to get a mentor. Find someone who is a good engineer and get them to review your code. If you don’t have a friend who fits the criteria, you can hire someone. It’s much less effective and more time consuming to try to learn all of the best practices on your own from blog posts and books.

Two engineering-related questions came in after last week’s post:

“What are your thoughts on no-code prototyping and testing?”

It’s a waste of time. I know this may be an unpopular opinion for some people, but no-code tools are often just as complicated to learn as code—except there is a low ceiling on what you can accomplish with no-code, and learning one no-code tool barely translates into any other tool. Code has a compounding advantage because the same patterns come up over and over again, and there is no limit to what you can build. I’m thankful that no-code wasn’t around when I was getting started, because I probably would have wasted a lot of time, and it would have been a dead end.

“What's the initial threshold for how much you should know to code before actually building things? There are things I don't know that I don't know, so how do I go about identifying them to have a baseline before I get into building mode where I can learn as I go?”

I reject the distinction between “learning as you go” and “establishing a baseline before you get started.”

You’re always going to ping-pong between acquiring skills and using them. Sometimes the loop is fast (e.g., looking up how to sort an array in JavaScript, then using it), and sometimes it’s much longer (e.g., deciding to use Ruby on Rails to create your web app, then buying a book and doing an extended tutorial before you write one line of code for your own app).

Even by asking this question you’re already getting started: you’re gathering information about how to approach the problem of building new products that people will love.

I got tripped up by the sense that it was costly to start over—and it was a relief when I got over it. It’s not true. You’ll learn so much faster if you feel free to start from scratch building the same idea 10 different times. And you should expect to do this. When you approach it this way, you give yourself permission to try to do the first step even though you know you’re probably going to screw it up. And that’s a good thing—because when you get stuck, you will have identified the gaps in your knowledge that are holding you back.

When I’ve spent too much time “building background knowledge” before I started building, I was procrastinating. I was psyched out by the daunting task in front of me, so I gave into the temptation to fiddle around. This same challenge will present itself to you over and over in life, in many different forms. It’s best to see it for what it is, stop fiddling around, and get started.

That’s not to say that tutorials and books are never useful. They are! But they are far more useful when you’ve already started to work on something and have encountered some problems that the tutorial can help you solve.

(By the way, this cycle never ends. Coding is a constant loop of looking stuff up every 5-10 minutes, writing code, then looking stuff up, over and over.)

6. Design

It’s impossible to fully separate design from programming. In other creative fields—architecture, furniture, apparel, music, etc.—there is a widely-accepted view that how things appear and how things are made go hand in hand. The constraints and capabilities of the material you are dealing with define what is possible. How could it be any other way?

But in software it’s controversial to suggest that designers should learn to code. The problem is that it’s not clear what is meant by “learn to code.” It’s logical—especially at big companies—for different workers to specialize in different parts of the creation process. I’m not suggesting that designers should be as good at programming as engineers, or that there should be no distinction between designer and engineer. But to create a good design, you need to know a lot about the material you are working with. Most designers agree.

When designing software, there’s a temptation to use off-the-shelf UI toolkits and CSS frameworks. I would be careful about this. Stock UI is never quite right for your specific needs, but it’s so easy to use and so close to “good enough” that it’s tempting to keep going with it. The furthest I go toward modularity is to use a good icon set, like Google Material Symbols or Apple’s SF Symbols library.

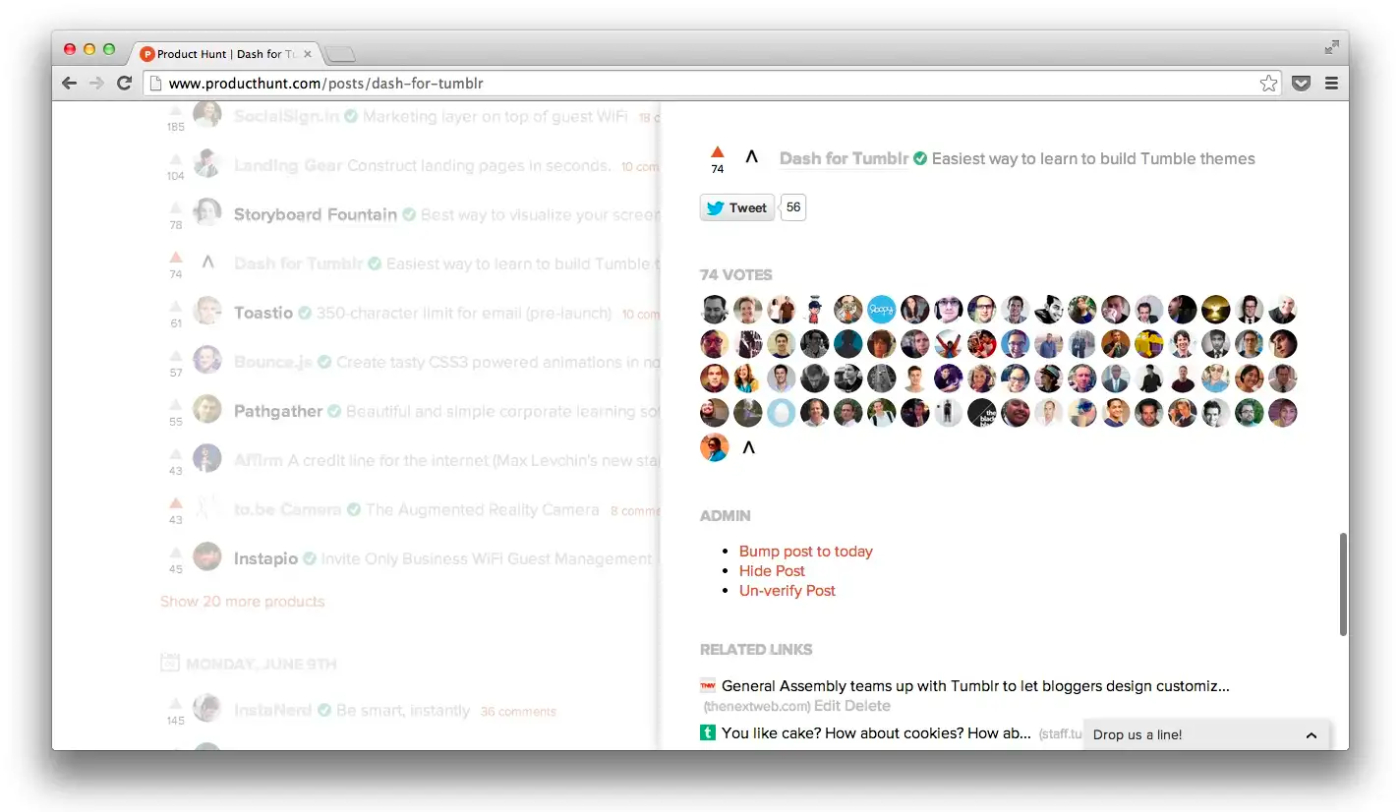

By avoiding stock UI frameworks, I’ve come up with some unique UI ideas. For example, when I was building the first version of Product Hunt, I realized that it felt high-friction to switch from browsing a list of products to viewing the comments. Instead of triggering a full page reload, I made the comments slide in from the right. Since then, other websites have adopted a similar pattern.

I find it easier and more satisfying to start from scratch than to wrestle with pre-made components. But the most important benefit is that it’s easier to achieve simplicity.

The more complex the design, the harder it is for a user to understand it. Have as few elements as possible—and make them count. The same principles I wrote about in the context of selecting which features to build also apply here: less is better, move quickly and based on your intuition without overthinking it, and show the product to users to uncover problems and solve them iteratively.

The big difference between product and design, though, is that with design it’s harder to “build for yourself” than it is with product because of the curse of knowledge. You as the creator will know exactly what happens when an icon is clicked, but users will have no idea what to expect. They’ll probably be afraid to click if they’re not sure what will happen—maybe it will mess something up. Also, when we’re using our own products, we subconsciously learn to avoid the “broken” parts in a way that users will not. If a certain action takes the server a long time to perform, you’ll use it less and avoid the frustrating wait that your users face when they click the button. Or if you do use it, your expectations will be properly set, so you won’t experience the annoyance as viscerally as your users will. Go out of your way to think about what it would be like if you came to the product fresh, with zero knowledge.

Over time you can develop your intuition to learn what people will understand and what they’ll find confusing, but the only way to improve is to observe people use your designs. When you’re sitting next to someone as they navigate your product, it becomes visceral just how confusing everything is. Your mirror neurons activate, and you can more easily empathize with what it feels like to see your product through the eyes of a new user.

Design is a little bit about aesthetics, but mostly about clarity. I want as little friction as possible between a user and their goals. The best way to do this is to pay close attention to how other websites and apps are built, and copy the patterns. For example, when people select text and hit “command+b” in a text editor, they expect the text to turn bold. When a tool works the way you expect it to, it feels great. And the way we think it “should” work is formed by our past experiences using other products.

The main role of aesthetics is to inspire trust and to support an overarching vibe. If a product feels like it has too much of the wrong personality, it can be a distraction. The best “personality” is not achieved by in-your-face choices like loud fonts or animations; instead, personality shines through when the interface allows the functionality to come through clearly. Such an interface makes the personality more about functionality than style, which is almost always better.

It might be a cliché to end on a Steve Jobs quote, but it’s perfectly apt: “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.”

In part III I cover getting and interpreting feedback, positioning, and launching.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!