.png)

Today’s piece is a bit different—it’s a short story by Dan Shipper that is a part of the book he’s writing. Read the first five pieces in this series, about the new worldview he's developed by writing, coding, and living with AI; how AI will impact science, business, and creativity; and how tools shape how we see the world. We’re off tomorrow for Veterans Day in the U.S. and will be back on Wednesday.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

For my money, the West began in an Athenian mansion in 430 B.C. Within it the philosopher Socrates debated the venerated teacher Protagoras about a simple question:

Can excellence be taught?

Not excellence in archery or carpentry—no one doubted that specialized skills could be taught—but the deeper kind of excellence the Greeks called aretḗ: the general excellence that makes a person a good citizen, a good decision-maker, and a fully realized human being.

We know about this debate because it was immortalized by Plato in his dialogue Protagoras, which tells us more or less what was argued:

Protagoras said “yes,” general excellence can be taught. Every moment of a child’s life, he argued, is training in excellence: Through imitation, story, and experience we learn how to live well.

Socrates, the philosopher, said “no.” And he argued it through a new form of thinking: philosophical inquiry. He asked Protagoras to define excellence—was excellence one thing or many? Were justice and courage part of excellence, or something separate?

Protagoras, one of the most famous and well-regarded teachers in Athens, could not define it. Each idea he offered collapsed in self-contradiction—as did his reputation. After all, how could he claim to teach aretḗ if he could not even say what it was?

This debate reminds me a lot of AI. For decades, we followed Socrates—trying to define intelligence, to find a theory of it that would lead to AGI. Then a small renegade group of researchers eschewed theory in favor of a different approach: training neural networks on vast amounts of data. And suddenly real machine intelligence was born.

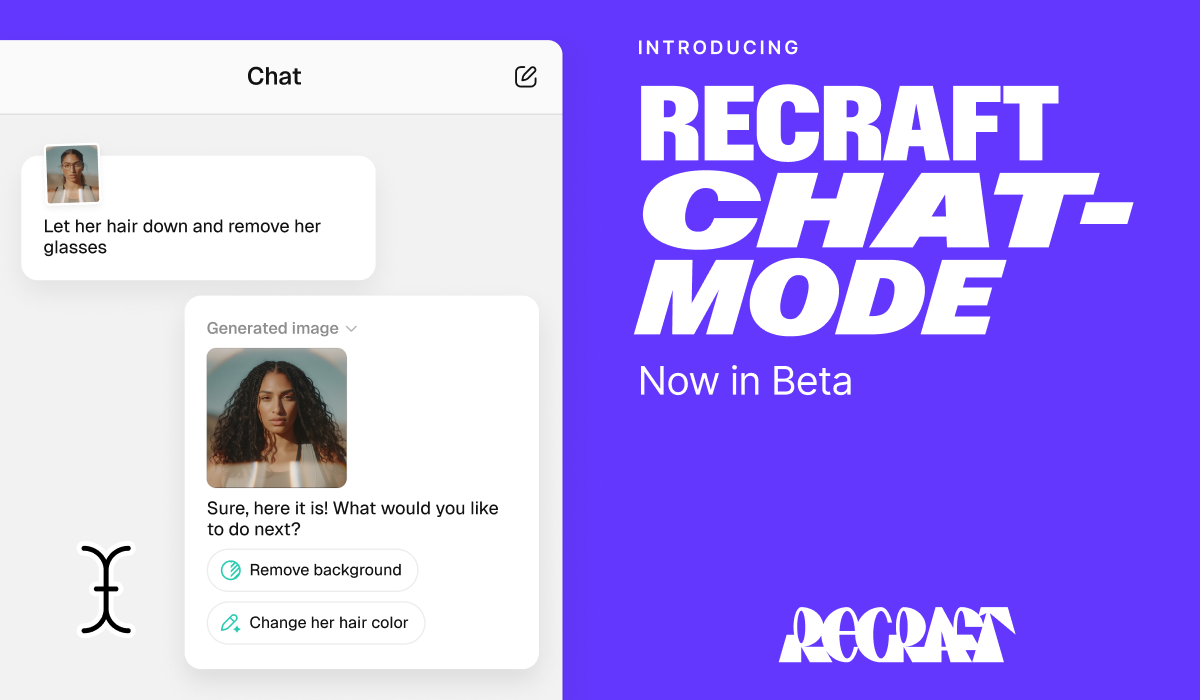

Design that actually listens

Recraft’s AI image generation and editing tools give you real control over your designs. Their new Chat Mode remembers your entire conversation history, letting you refine and iterate logos, branding, and marketing assets naturally. Professional designers at Netflix and Airbus already use it to stay consistent across every revision.

These systems, in their strange way, are an answer to Socrates’s question about how we can teach what we cannot define. And in their own way they vindicate Protagoras: They show us that excellence can be learned through training, and we can become excellent at things we can’t fully explain.

I’ve always wondered what happened to Protagoras after that night in Athens. I wondered—in the same way we discovered neural networks—whether he figured out how to teach what can’t be defined. And so I wrote a story about it.

When the lamps were finally extinguished in Callias‘s house and the great men had made their way home, Protagoras walked the dark streets of Athens.

For 40 years he had wandered Greece teaching excellence. He had helped craft laws for distant cities and advised Pericles himself. But Socrates’s question haunted him. He could recognize excellence, nurture it, even teach it. But define it? Grasp it in his hands and show another exactly what it was? No.

In the years that followed, Protagoras circled on this question. He gave up teaching in the houses of Athens’s wealthiest citizens. The Peloponnesian War broke out, and the boys he had taught marched off to battle. But Protagoras felt nothing because he saw nothing; the faces of those men were like masks to him, indistinct and abstract.

Eventually, Protagoras exchanged his flowing purple robe for a rough one, as he no longer used his eyes. Eyes in disuse, his sight itself began to fade. Slowly, Protagoras went completely blind.

In 430 B.C., Athens was struck by a plague. The sick and dying lay in the streets. Protagoras sought refuge in a temple of Hermes, god of boundaries, messenger of the gods, guide to the underworld, and protector of the blind. The temple sat at the first milestone from Athens, where two roads met. It was no Acropolis, just a mound of stones—a herma—to mark the junction, with a crude shelter built around it. The shelter had walls of wood scavenged from carts abandoned on the dusty road, and a patchwork roof made of tile and thatch carefully pitched so that rain ran down into collection jars. Merchants met at the herma to make offerings to its namesake god, who protected travelers and businessmen alike, and to exchange goods from far-off lands to be sold in the markets at Athens.

The shelter housed a gang of orphaned children, blinded by plague but still alive, their families killed by the disease that devastated their city. They took offerings from the travelers who passed by, sang hymns to Hermes, and sat all day in the hot, sun-hardened dirt next to the temple.

“By Hermes himself, I’ll pay double the market price. Double!” The high-pitched voice cracked through the herb-soaked cloth covering its owner’s mouth.

The plea was directed at a Phoenician trader who’d set up shop near the temple. In the surrounding darkness, Protagoras recognized the voice as belonging to Callias, the man whose mansion had housed his fateful debate with Socrates.

“Pure white hellebore, from the mountains,” said the Phoenician. His voice was deep and jagged. “I already have a buyer in the city, but if you can pay me now I will forget about him.”

Callias clutched a leather pouch to his chest with shaking hands. For three weeks he’d been trying to buy hellebore root for his granddaughter’s fever. “Yes, but only if you’ll swear they’re real.”

They stood far apart, as plague custom demanded, their words carrying across the dusty crossroads. The morning sun cast their shadows toward the herma, where the blind children huddled, listening.

“And how will I know that what you offer to pay me with is real?” said the Phoenician. “I don’t know you. Why would I risk plague to test your silver with my teeth.”

“The silver is good,” Protagoras said from the shelter’s doorway. “I’ve known Callias since he was a boy.”

The Phoenician turned toward the voice. “Protagoras? The sophist?” A pause. “Then you know about such things. Come, test this silver yourself, and the hellebore too. Your word would be enough.”

“These days I keep my distance.” Protagoras gestured at the space between them, thick with the miasma of plague. “As we all must.”

“A wise man. But without someone to test it, there can be no trade. Not with death in the air,” said the Phoenician as if casually flicking a fly off of his arm. He began to pack away his goods. “Perhaps when the plague passes.”

“When the plague passes,” Callias repeated hollowly, “my granddaughter...”

Protagoras listened to their footsteps fade. Behind him, the orphan children played quietly, fearless of the plague that had already marked them. They could touch what he could not. But they were uneducated and inexperienced.

Socrates’s question echoed once again in his mind: How can you teach what you cannot define? Protagoras could feel the specific weight of pure silver, how it yielded slightly under pressure in a way that lead never quite matched. He knew the subtle ridges of a genuine coin’s edge, worn smooth in exactly the right places from years of handling. He could detect the distinctive way real white hellebore’s fibers separated when gently pulled apart, unlike the too-clean break of common look-alikes, and the specific density when squeezed, the slight stickiness of its sap.

How could he explain these things? How could he define them precisely? True and false lived in his hands after decades of practice. But what he spoke would only be a shadow of what he knew.

That night, Protagoras sat in darkness at the shrine’s threshold, listening to the soft breathing of sleeping children. Somewhere in Athens, a girl burned with fever, waiting for medicine that might save her. And here he was, useless, with knowledge he couldn’t pass on.

His fingers knew. But how to teach fingers to know?

Protagoras woke at dawn to the sound of singing.

The orphans were singing hymns to Hermes. Their voices danced together, weaving up and down in complex harmonies as they listened and responded to each other. He could feel the chords ring true in his ears, his chest—his whole body. Each note as precise as from a lyre tuned by a master.

One child’s voice wavered off-key, slightly flat. It stuck out like a fly on a fig. The eldest girl, who led their songs, stopped them and corrected the child.

“No, no,” the eldest girl said gently. “Listen carefully.” She sang the phrase again, her voice clear and true. “Try to keep your voice up, like this.” She demonstrated once more.

The younger child attempted it again, straining to match the note.

“Better,” the eldest girl encouraged. “Again.”

They repeated the phrase several times, the younger voice gradually finding the right pitch, until finally their voices blended perfectly.

And suddenly, an idea occurred to Protagoras.

“Bring me two pieces of silver,” he said to the eldest girl. “One true, one false.”

. . .

The orphans sat in a circle in the dust. Each had a single finger on a true silver coin that gleamed in the afternoon sun.

“Now,” Protagoras said softly, “sing what you feel beneath your finger. Just a single note. Don’t think about it. Let your finger guide your voice.”

The children hesitated. Then the youngest, a girl of perhaps seven, began to sing—tentatively at first, then with growing confidence. Her note wavered.

The next child joined, his voice finding a different pitch. One by one they added their voices until the air hummed with their song.

The sound was terrible. Discordant.

“Good,” said Protagoras. He spoke to the youngest child, whose finger rested on one edge of the coin. “Sing your note again.”

The child sang, and Protagoras could tell she was singing too sharp.

“When you feel this beneath your finger, you must sing a little bit lower, for the note to be true,” he said.

“When I feel what, though?” said the child. “I feel an edge, ridges, hard metal, flatness.”

“All of those, and more,” said Protagoras. “Do not try to define what it is that makes you sing a note. Just sing what you feel, and I will tell you if you are too high, or too low. Eventually you will know it yourself.”

He did this again with each child in the circle, each touching their own part of the coin with a single finger. He lowered sharp notes and raised flat ones.

“Now, sing again,” he said when he had finished with the last child. A beautiful, bright chord rose from the circle and echoed across the dusty road.

Protagoras smiled. He told the youngest girl to pick up the coin in the center of the circle and replace it with a new one which he knew to be false.

“We start again,” he said.

The youngest child went first again. She felt flatness and coolness beneath her finger. She sang the same note that she had for pure silver.

“Wrong,” said Protagoras. “You are thinking too much. Your job is not to know what silver feels like. It is just to sing your feeling into one pure note.”

She relaxed and tried again, trying to sing touch into song. A note rang out from her mouth, close to the note she sang for pure silver—but something was slightly off. “Good,” said Protagoras.

He went around the circle, repeating the ritual for each child. “Now sing again,” he said.

Another chord rang out in the twilight, similar to pure silver’s sound, but in a minor, melancholy key. None of the orphans could know from the small piece of coin they touched what kind of metal was under their finger. But together, their music did.

Each morning for the next few days, the sun rose on a circle of small figures standing barefoot in the hardened earth outside Hermes’s shrine, hands outstretched, each hand touching only a sliver of whatever object Protagoras placed before them.

He found silver coins broken in half which produced a haunting sound—the pure notes of silver split by sharp, biting tones from the jagged edges. The chord was silver’s bright song, but wounded—like a familiar melody played as a funeral dirge. He found silver ingots from the mines at Laurium carried by merchants passing through. These produced silver’s song, but fuller at many octaves at once. He found delicate silver earrings, their surfaces etched with intricate patterns, which sang silver’s melody but with subtle harmonics dancing above the main chord—silver’s song adorned with grace notes, each tiny worked detail adding its own crystalline tone to the whole.

But when Protagoras introduced gold, everything broke again. Some children defaulted to silver’s chord; others’ voices wobbled so wildly that the merchants paused to stare. Protagoras proceeded by the same method he had with silver: He worked with each child individually, helping them find the unique resonance of gold beneath their fingertips. Gold sang deeper, richer notes than silver—a warm, yellow sound that filled the air like a noon-day sun.

As word spread that “the blind children of Hermes” could judge metals by song, merchants came from Athens bearing coins. Anxious to avoid plague, they tossed their pouches into the dust, stepping back.

The children didn’t speak of “silver” or “gold,” but rather sang their findings in pure tones. Merchants soon trusted their musical verdicts more than traditional tests. But Protagoras was not satisfied. He knew that somewhere in Athens, Callias’s granddaughter still burned with fever.

“Today we try something new,” he told the children. He placed several roots—dried with age, their healing power spent—in the dust before them. “These are hellebore roots. Some true, some false.”

The children reached out to touch them, but Protagoras stopped them. “Wait,” he said. “First, remember the song of silver. How it feels under your fingers, how that feeling becomes sound in your throat. Now touch these roots. Let your fingers remember silver, but sing what’s different.”

The children touched the roots. Their first attempts were cacophonous—some singing silver’s song, others finding new notes that clashed and grated. But Protagoras worked with them, adjusting their voices just as he had with silver. Slowly, a new chord emerged, different from silver’s song, but just as true.

“Good,” said Protagoras. “Now this one.” He replaced the true hellebore with false.

Days passed. The children learned to sing not just metals and roots, but woods, cloths, oils, and spices. Each material had its own song, but they were not separate songs. They were variations, each one building on what came before. The song of cedar contained echoes of oak’s song. The song of saffron whispered of turmeric. Protagoras knew he had discovered something extraordinary.

Then one morning, Protagoras heard a familiar voice by the shrine.

“Pure white hellebore,” said the Phoenician merchant. “From the mountains.”

Protagoras gestured to the children. They gathered around the root the Phoenician had placed in the dust. Their small fingers touched it gently. Then they began to sing.

The chord that rose from their circle was wrong—discordant and false. It contained notes of cheaper roots, of clever imitations. The children’s faces twisted as they sang, as if tasting something bitter.

“This is not white hellebore,” said Protagoras quietly.

The Phoenician cursed and gathered his goods quickly, disappearing down the road before Callias could call for the guards.

Three days later, another merchant came. The children touched his hellebore root and sang a pure, clear chord that made the air itself seem to shimmer. Callias bought it and rushed back to Athens. A week later, he returned to make an offering at the shrine. His granddaughter’s fever had broken.

As word spread that “the blind children of Hermes” could judge truth by song, merchants came, first from Athens, then beyond, bearing coins and goods, setting them on the sun-hardened dirt by the shrine. The merchants soon trusted the children’s verdicts more than traditional tests, and some would travel days out of their way to obtain them. Some tried to learn the children’s art, but none could master it. For the children had not learned rules that could be written down and followed. They didn’t speak of “silver” or “gold,” but rather sang their findings in pure tones. They had learned, under the guidance of an aging sophist, how truth feels under the fingers, how it resonates in the body, how it emerges in harmony when many voices join together.

Collectively, their voices grasped something too big for any one of them to know.

Dan Shipper is the cofounder and CEO of Every, where he writes the Chain of Thought column and hosts the podcast AI & I. You can follow him on X at @danshipper and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We build AI tools for readers like you. Write brilliantly with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora. Dictate effortlessly with Monologue.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

For sponsorship opportunities, reach out to sponsorships@every.to.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I love how this story shows the value of this kind of learning (this kind of knowledge). Arising directly from experience, strengthened (reinforced, confirmed) by shared experience and compared results. Great analogy for AI modeling.

But I still sense this slit that never seems to go away - the one Socrates was using in his argument. While I think Aristotle would argue that the Protagorean form of knowledge is the only one we have access to - concepts arise from experience (there is no form of a chair, just the notion of chair we get from encountering many chairs and not chairs), Plato would argue that there is more. There are aspects that have not been well represented in our experience, yet are still true, and we can work to discover them, but not in the way the children were taught. I wonder if there is an analogy, a similar story, that would be Socrates' answer to this - how there is still more, and how it might be learned. Would this highlight something the current AI approach can't reach?

I've been picturing AI aids the way I used to think about what I called the two infinities on my sixth grade ruler. There were the infinities between all the marks within the 12 inches. AI can help us find those, I think. Then there are the infinities beyond the ends of the foot - in both directions. I'm not sure our current approach can help with those.

@semery Thanks for reading and the thoughtful comment! For me the story’s not mainly about empiricism (though that is one valid reading) but about distributed, inarticulable knowledge—the kind that can’t be fully explained or formalized. Plato’s Forms actually fit inside of that, and I think high-dimensional spaces are quite an interesting version of what he was talking about

In this case, the story is about recognizing something empirical, but I would bet neural networks can help us find the infinities beyond the ends of the ruler, too! Maybe I should write about that next :)

I love this unexpected post! I have been delighting myself bringing concepts, even ancient philosophical concepts, to life using AI to stage dialogues. But this is a full-fledged story, and a quite captivating one at that. Excited to read the next entries. PS Why add bold to the character names in a short story?

@federicoescobarcordoba glad you liked it! the bold is just our house style :)

@danshipper This piece rekindled an unapologetic desire to revisit the Apology! Speaking of craft, I noticed a couple of tiny style details you might want to glance at (“Callias‘s house” vs. “Callias’s house” at the beginning, and a missing question mark after “Why would I risk plague to test your silver with my teeth”).

If you ever decide to nudge this further toward literary fiction, Janet Burroway and Stephen King both have wonderful thoughts on dialogue tags and adverbs in Writing Fiction and On Writing, respectively. That said, I enjoyed how your prose carries the ideas—form serving philosophy.

And just a small note of curiosity: the line “His fingers knew. But how to teach fingers to know?” made me wonder. It’s beautifully phrased as is, though “But how to make other fingers know?” might make the meaning a touch clearer.

Bravo -- this story is the best explanation-by-analogy of LLMs for the lay person that I've encountered so far. But like all good explanations (see David Deutsch's book "The Beginning of Infinity", 2011), it suggest, or makes explicit, additional areas or aspects that are yet unknown, uncovered, unexplained; specifically, what is being perceived, or experienced, to change the child's learned tone from "discordant" for true silver or hellebore to "pure"? Protagoras' admonition to "sing what's different" is instructional, encouraging, but is not itself an explanation (of *what* to do). Scientific theory progresses, advances, by the production (by people) of better and better (improving, more detailed, more accurate, more corresponding to...) explanations, yet we're told that how LLMs work defies analysis and explanation (unlike algorithmic/procedural computing). Yet can we not expect that the very success of LLM/AI chatbot/products will ultimately yield to new insights, and a "better explanation" (theory) of LLM computation? I'm an optimist, now (formerly a skeptic)...

Thanks, Dan, for this excellent, thought-provoking piece!

@lorin thanks for reading and commenting! in a complex system with multi-finality and equi-finality like a neural network you CAN find hard to vary explanations, however they’re not universal. so you can find the conditions under which a system might shift to a discordant note in a particular situation—but because the system is equifinal (multiple paths to the same result) a hard to vary explanation that is GENERAL is by definition not possible, and imo not a good way to work with this kind of system. I do think we can expect better explanations and theory from them, just that they also point to the necessary limitations of theory

great question how can you teach what you cannot define......we are missing what should be at the top of the AI pyramid and that is love....how to you teach it ..by example and showing it and that bring wisdom from seeing what is true and what is not....reality will change that definition as it evolves

Fascinating story. Linking touch to singing is an ingenious move. It makes me think about the nature of tacit knowledge: does it mean knowledge that cannot be articulated by anyone, or just not by the particular teacher? In this case, I could imagine that with modern understanding of anatomy and psychology, the translation from touch to voice could, at least in theory, be articulated, right?

@Haihao.wu thanks for reading! yes you could definitely describe (theoretically) the translation from touch to voice for a single child—but that's just plumbing and would be unique to that particular child. it wouldn't tell you much about which notes mean what.

imo, it's not that tacit knowledge can't be articulated it just can't be fully and completely articulated and neural networks are a better way of transmitting it than explanations are

My dude... Awesome...